Armitage Shanks

Assemble’s Louis Schulz in conversation Alena Pavan, Dylan Maeers, and David Meiklejohn

Pt I - Bathroom

Dylan Maeers:

Reflecting on the talk you gave for Armitage Shanks in 2014, you posited that the ceramic water closet could be one of the few architectural elements which “has not felt the effects of postmodernism.” If postmodernism can indeed be understood to challenge the dictum of ‘form follows function,’ is it possible to make a postmodern toilet? And, if so, as an object whose form is so intrinsically linked with its function, what might a postmodern toilet look like?

Louis Schulz:

The Sponge Bob toilet would be one example. Apart from the victorian examples given in the talk, those created in the heyday of sanitary pottery that look quite different from how we imagine toilets now, I think it’s totally possible to add decorative, postmodern elements to toilets. Not only was it previously very common within the pottery of the toilet, even now, you still get some people having a bit of fun with the toilet seat.

![]()

DM:

So then is your ambition the intentional subversion of that traditional image of sterility?

LS:

It’s not intended to make it less “sterile looking.” I don’t personally have a problem with people wanting to feel like their toilet is clean. But I guess it can lead to an obsession or a reinforcement of an idea that it has to look like that. Or that it has to be like that. I mean when we used to run a cafe and the health inspectors would come around, they didn’t care about the toilets, because it wasn’t a major means of disease transmission compared to food handling.

Toilets have come to embody a perception of cleanliness and sterility, it’s a tradition. With toilets, it’s much more about expectation. If people go into a cubicle and see something that they’ve never seen before, they’ll be like, “Whoah!” Perhaps even scared to engage it, and that’s why toilet design tends to be very conservative.

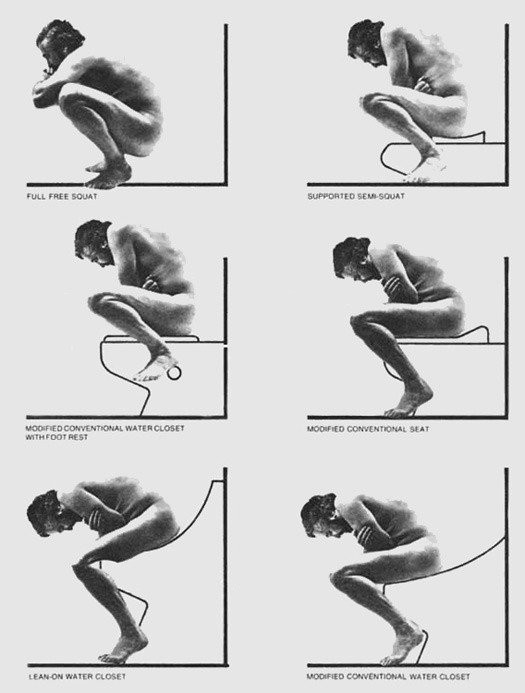

Have you read The Bathroom by Alexander Kira? It’s the bible. In it, Kira totally reconsiders the toilet. Like, if you don’t have to have men standing up to piss, toilet design can change quite a lot. But as soon as you introduce something that looks different to what people expect, they recoil.

Toilets have come to embody a perception of cleanliness and sterility, it’s a tradition. With toilets, it’s much more about expectation. If people go into a cubicle and see something that they’ve never seen before, they’ll be like, “Whoah!” Perhaps even scared to engage it, and that’s why toilet design tends to be very conservative.

Have you read The Bathroom by Alexander Kira? It’s the bible. In it, Kira totally reconsiders the toilet. Like, if you don’t have to have men standing up to piss, toilet design can change quite a lot. But as soon as you introduce something that looks different to what people expect, they recoil.

“The Bathroom” by Alexander Kira (1976)

Alena Pavan:

Yeah, it’s too radical.

LS:

Exactly. So you get things like the QWERTY keyboard. It’s not the best, but it’s just what people are used to.

AP:

In regards to the curation of the Bathers project at the DKUK hair salon/exhibition space; while the impetus for selecting this venue seems clear (as the project is described as a re-envisioning of the ceramic toilet “as a cultural destination”), was it important to Assemble that the work was not exhibited in a “traditional,” more formal gallery setting?

LS

I think you got it right. It’s to do with it not being in itself an item of decoration, of the toilet space. If you’re going in there to do your business in the toilet but you know there’s something there for you, maybe a joke book, an encyclopedia, or maybe it’s the toilet itself adorned with funny miniature people. There’s something quite nerve-wracking about putting art in a gallery. Principally because the only purpose of you being in there is to see this object. So this object has to do so much and has to be everything. It’s something that I find very difficult to imagine just wanting to go and look at, an object. I think the venue selection was more to do with it being kind of a sideshow. Just to make it a little bit more easy-going. And so having a purpose other than just being a thing in itself. Which is sometimes a little bit pompous.

![]() Bathers at DKUK, 2019

Bathers at DKUK, 2019

Bathers at DKUK, 2019

Bathers at DKUK, 2019DM:

Was the attitude towards exhibiting in the DKUK salon at all tied to the juxtaposition of its nature as a public space, compared to that of the formal gallery?

LS:

To be honest, I don’t think the DKUK salon was necessarily our ideal scenario in which to exhibit. It was just opportunism. We were asked if we would like to exhibit something in the toilet and it was like, a bit of a joke as well. We had done a toilet. It’s in a toilet. I don’t know exactly the price point of the hair salon, but suffice it to say, the type of people that would feel welcome in an art gallery, would feel welcome in the DKUK hair salon, and the people that don’t, won’t. I don’t think it’s something that we would be singing from the rooftops. Maybe having something small in a toilet allows us to live with ourselves in that situation.

AP:

Still, it’s a bit curious to me. Did you find that exhibiting in the salon, which doesn’t have the same number of precedents as a conventional gallery, makes it feel less curated, or more curated? Because you suddenly had to figure out a novel way to exhibit the work.

LS:

Yeah. It’s a funny one, isn’t it? Obviously, if you had it just off to the side in a gallery, in a way, it’s more inconspicuous than putting it in this crazy location. And especially due to the fact that this hair salon, as far as I’m aware, their selling point is that instead of looking in a mirror you look at a painting you’re meant to have it in front of you.

AP:

Yeah, I think I remember that.

LS:

So I guess in a way they’re representing themselves as mold breakers in the way that art is presented and consumed. But, I don’t know if we really buy that as such. For us, we’re just something to look at while you’re doing a poo.

![]() Bathers, 2019

Bathers, 2019

Bathers, 2019

Bathers, 2019DM:

Something we like about the attention given to the ceramic toilet in Bathers is the sense of identity which is assigned to each individual product as a direct result of a highly experimental process. This feels timely in the space of the bathroom, especially with all the issues it touches in the realm of gender and identity. While trying to avoid fetishizing marks of making too much, why is it important to Assemble that each piece is a result of experimentation?

LS:

It’s something we talk about quite a lot. At this point in time, it feels like what you’re presented with is a choice between something mass-manufactured, probably in a room full of robots, versus a crafted individually made piece. It’s an Amazon vs Etsy dichotomy. Obviously we acknowledge that people who have a grasp of the manufacturing process understand that there is a huge spectrum of diverse processes but I guess it’s this question about how we experiment with the manufacturing process, and also how we speak about the craft that is actually involved in mass manufacturing. Given that this is an Armitage Shanks project, we’re aligning ourselves with the mass-manufactured side of things -- but what we’re trying to speak about is the crafting process that is inherent in that mass-maufacturing process.

Most of the time with mass-manufactured products it’s amazing the craft that goes into making even the most every day or seemingly mass-produced objects. Manufacturing is much less automated than people probably imagine. There are a lot more people involved, and those people tend to be very knowledgeable about the things that they’re making. It’s not like Metropolis pulling a crank or whatever. We were only able to make these products because Armitage Shanks showed us how to make them. We came with an idea, but they had this archive of hundreds of pieces that were experiments they had done in the past.

So we tried to make it about Armitage Shanks as much as possible. Have you heard our radio show, The Sympathy of Things? That was also kind of tied into it but it’s difficult, because we’re the ones with cultural capital, to try not to come across like we’re taking credit for it while also speaking about the craft that has been built in many cases, over centuries.

![]() Armitage Shanks, 2017

Armitage Shanks, 2017

Most of the time with mass-manufactured products it’s amazing the craft that goes into making even the most every day or seemingly mass-produced objects. Manufacturing is much less automated than people probably imagine. There are a lot more people involved, and those people tend to be very knowledgeable about the things that they’re making. It’s not like Metropolis pulling a crank or whatever. We were only able to make these products because Armitage Shanks showed us how to make them. We came with an idea, but they had this archive of hundreds of pieces that were experiments they had done in the past.

So we tried to make it about Armitage Shanks as much as possible. Have you heard our radio show, The Sympathy of Things? That was also kind of tied into it but it’s difficult, because we’re the ones with cultural capital, to try not to come across like we’re taking credit for it while also speaking about the craft that has been built in many cases, over centuries.

Armitage Shanks, 2017

Armitage Shanks, 2017

DM:

That makes a lot of sense. In every example of that Amazon scaling process, we tend to overlook the degree of work and experimentation that would have taken place. That it’s sort of the end-stage in moving forward with research and design.

AP:

As a practice that values the DIY ethic, often prototyping and even fabricating full-scale buildings yourselves, when do you start to let go of being heavily involved in a process such as the one used for this Armitage Shanks toilet, and pass projects off to others?

LS:

I think it just depends on the project, really. When you read it like that, it may come across like we’re obsessed with controlling every aspect of a project or a creation, but I don’t feel like that’s our position.

We think of ourselves as taking on different roles in different situations depending on what’s appropriate at the time.

Construction and making is a tradition of our organization that we’ve had from the beginning and, while we can philosophize, it’s also in the same way that it’s designed. I find it funny that it’s always questioned -- the construction and the building part of our process -- as an additional process, while the design part is accepted as being the elemental or core piece that wouldn’t require questioning. But of course, it totally depends.

Obviously The Bathers one is a small toilet, but we tried to do big ones as well. The kind of equipment and the expertise that they have at the Armitage Shanks factory was critical. We actually tried making big toilets in our workshop as well and it was really hard. They gave us the plaster mold because to make the molds also takes a huge amount of work and design expertise. Beyond the factory floor, there are guys who spend their whole lives doing the 3D modeling and worrying about how it is going to sag in the kiln, how thin can they make it, what shapes are possible etc. Some of them are joined; some of them are cast in pieces and then joined together. They have to think about that, and there are loads of things that we could never do. It’s about working with people like that to try to do fun and interesting projects that we can collaborate on.

![]()

![]() Armitage Shanks toilet molding, 2017

Armitage Shanks toilet molding, 2017

Collaboration in itself can also be a bit of a sticky topic as well because sometimes, who gets to be a “collaborator” and who is just a “worker,” or a non-mentioned person is always hard. For instance, Armitage Shanks is a bit different because we only really worked with Armitage Shanks, but if we do a building project, did we collaborate with the plasterer? Of course, we did collaborate with the plasterer, and you think, “well we should name everyone we collaborate with,” but some people don’t care about necessarily being named on the website. For some people it’s important, for some it’s not. It’s a minefield. It’s a minefield more in terms of its expression and how it’s spoken about than the kind of everyday reality of collaborating on a project, which is not in itself difficult.

Construction and making is a tradition of our organization that we’ve had from the beginning and, while we can philosophize, it’s also in the same way that it’s designed. I find it funny that it’s always questioned -- the construction and the building part of our process -- as an additional process, while the design part is accepted as being the elemental or core piece that wouldn’t require questioning. But of course, it totally depends.

Obviously The Bathers one is a small toilet, but we tried to do big ones as well. The kind of equipment and the expertise that they have at the Armitage Shanks factory was critical. We actually tried making big toilets in our workshop as well and it was really hard. They gave us the plaster mold because to make the molds also takes a huge amount of work and design expertise. Beyond the factory floor, there are guys who spend their whole lives doing the 3D modeling and worrying about how it is going to sag in the kiln, how thin can they make it, what shapes are possible etc. Some of them are joined; some of them are cast in pieces and then joined together. They have to think about that, and there are loads of things that we could never do. It’s about working with people like that to try to do fun and interesting projects that we can collaborate on.

Collaboration in itself can also be a bit of a sticky topic as well because sometimes, who gets to be a “collaborator” and who is just a “worker,” or a non-mentioned person is always hard. For instance, Armitage Shanks is a bit different because we only really worked with Armitage Shanks, but if we do a building project, did we collaborate with the plasterer? Of course, we did collaborate with the plasterer, and you think, “well we should name everyone we collaborate with,” but some people don’t care about necessarily being named on the website. For some people it’s important, for some it’s not. It’s a minefield. It’s a minefield more in terms of its expression and how it’s spoken about than the kind of everyday reality of collaborating on a project, which is not in itself difficult.

AP:

Assemble has self-described as “professional amateurs”, so I wonder if this ethos permeates not only into the way you frame a project from the start but also how a final product could be interpreted by others approaching their own crafts. This is no doubt different on a project-to-project basis, so maybe you could speak specifically about this particular marbling process and its outcome. Do you see part of the experimentation, happy accidents, whatever-you-wish-to-call-it, in a project like the Armitage Shanks collaboration as a way to discover new methodologies that might become more approachable to a larger public audience?

LS:

I guess it’s about taking different skills, taking everybody’s input seriously, and thinking about how it might be used to make the project more interesting. If you don’t collaborate with the electrician, then the electrician is just going to do what he always does, which is totally understandable; but if you collaborate with an electrician, then maybe you can do something completely novel. Maybe you can do the wiring containment and trunking and conduit in a really interesting way.

Pt II: Kitchen

Splatware

SplatwareDM:

Carrying on the broader theme of Assemble’s approach to practice we’d like to step away from Bathers and Armitage Shanks and talk about some of your other projects. Generally, we’ve been speaking about the bathroom and its relationship to ceramics and craft, but what are Assemble’s ideas surrounding the kitchen? If you’re re-purposing the toilet to make the bathroom a cultural destination, what’s happening in the kitchen?

LS:

I don’t think we have spent too much time thinking about the kitchen. Our studio is shared with a whole building of about 50 other people; we did the renovation of the building a couple of years ago and put in a big kitchen because we’d had one in our original building. We moved in 2016/2017, but from 2011 to 2016 we had a different building. That was one in which we had a pizzeria for a while, so we always had this big kitchen and did this lunch rotation.

The pizzeria didn’t work out, so we closed that -- but then there wasn’t anywhere to get lunch. So in our new building, it was obvious to put in a big kitchen or cooking facilities. We still have this routine and the kitchen is packed full of people at lunchtime. We carve out time for lunch and everyone sits down and has a proper meal -- none of this sandwich at your desk kind of stuff. It’s a funny one, because also now you have the like tech company buffet things, where even having the food becomes some kind of symbol of working harder. Because you’re constantly fed 24/7, you can just work all the time. That’s a bit annoying. The idea for us is that it’s the time in the day when you stop working, and that’s the purpose of it.

The pizzeria didn’t work out, so we closed that -- but then there wasn’t anywhere to get lunch. So in our new building, it was obvious to put in a big kitchen or cooking facilities. We still have this routine and the kitchen is packed full of people at lunchtime. We carve out time for lunch and everyone sits down and has a proper meal -- none of this sandwich at your desk kind of stuff. It’s a funny one, because also now you have the like tech company buffet things, where even having the food becomes some kind of symbol of working harder. Because you’re constantly fed 24/7, you can just work all the time. That’s a bit annoying. The idea for us is that it’s the time in the day when you stop working, and that’s the purpose of it.

DM:

Is the difference then, between the communal kitchen and the buffet, actually rooted in the idea of coming together through an act of collaborative making rather than through an act of consumption?

LS:

Yeah, that’s a fair point. It’s a set time, we don’t have a chef and it’s on a rotation so everyone’s gotta do it. It’s not particularly abundant either. Just a normal plate of food. I haven’t actually been to any of these Google buffet things but they’re in people’s consciousness now; this idea of food being

available in an office environment. But for the majority of people, certainly, in the UK you’re lucky if you get a microwave in the office.

available in an office environment. But for the majority of people, certainly, in the UK you’re lucky if you get a microwave in the office.

AP:

Is there any connection between the labor associated with food preparation, and the aesthetic of the ceramics produced for communal kitchenware (thinking here of Splatware, pieces made for Rules of Production, etc)? At first glance the pieces are visibly hand-made, and completely unique from one another, which makes one think of the time and skills associated with traditional handcrafting. It’s interesting though, because they’ve actually been streamlined for production, whether it’s through community workshops (Blackhorse) or industrial processes (Splatware). Is this something Assemble did intentionally?

LS:

Blackhorse Workshop is just a provision of equipment. People just go there and can make whatever they want. It’s like woodwork machinery, welding equipment, sewing equipment, etc. It’s rooted in the idea of the tool library. You can go in and do a course or something, but people don’t produce stuff to a set design. Different people use it for different reasons, whether it’s fixing their chairs, running a little mini business, or just learning how to do something like welding or carpentry.

With Splatware and The Rules of Production, they build on the same ideas as Armitage Shanks collaboration, and before that stuff that we did the Yardhouse tiles. I’m sure there’s stuff before that as well.

I was talking before about how the expression of something being handmade can also be applied to an industrial process or a manufacturing process. It’s the same kind of idea. Yeah, it’s definitely an intention that they’re visibly handmade, absolutely.

![]()

![]()

Splatware raw clay

Obviously with Splatware or with many of the other things that we’ve done the simple way to produce variation is by having a form and basically changing the colour. The Yardhouse was just different colours while something like Splatware uses blobs of clay in different colours while the Armitage Shanks toilet was liquid clay, different colours mixing together.

The Rules of Production is more about form and how we can use a mass production technique to produce a multitude of different forms. There’s also A/D/O, a New York project that we did, where we basically made a lot of useless stuff. We had this extruder and you can make dies for it, different shaped things that it can squeeze out, and we just created tons of different dies and then made as many different things as possible. Mostly cups and vases and stuff like that. It wasn’t the most successful project ever, but it was quite fun. That’s the main thing.

With Splatware and The Rules of Production, they build on the same ideas as Armitage Shanks collaboration, and before that stuff that we did the Yardhouse tiles. I’m sure there’s stuff before that as well.

I was talking before about how the expression of something being handmade can also be applied to an industrial process or a manufacturing process. It’s the same kind of idea. Yeah, it’s definitely an intention that they’re visibly handmade, absolutely.

Splatware raw clay

Obviously with Splatware or with many of the other things that we’ve done the simple way to produce variation is by having a form and basically changing the colour. The Yardhouse was just different colours while something like Splatware uses blobs of clay in different colours while the Armitage Shanks toilet was liquid clay, different colours mixing together.

The Rules of Production is more about form and how we can use a mass production technique to produce a multitude of different forms. There’s also A/D/O, a New York project that we did, where we basically made a lot of useless stuff. We had this extruder and you can make dies for it, different shaped things that it can squeeze out, and we just created tons of different dies and then made as many different things as possible. Mostly cups and vases and stuff like that. It wasn’t the most successful project ever, but it was quite fun. That’s the main thing.

AP:

In the Rules of Production, the slip casting technique and interchangeable moulds made for a fairly rigid, almost “industrialized” fabrication process that acts to standardize the individual crafter’s hand while still offering controlled variations within the system.

Who did you engage with to develop knowledge of this fabrication process and was the nature of Assembles role as a conduit between this craft source and the greater public?

LS:

So basically, the Granby Workshop did that project. Granby Workshop is an Assemble business, but the people who work there do it full time. It’s a ceramics business. So they know what they’re doing. It’s something that came out of the Turner Prize. Lewis Jones, set up the workshop as a way of trying to give back.

We had done the houses in Granby, but many of the commercial properties were empty and there’s still a lack of jobs in the area. A lot of manufacturing jobs going overseas and things so the idea was, could we set up a new manufacturing business in Granby and employ local people and see what came of it? So that’s what we did. Lewis moved to Liverpool to do that in 2015 and has continued to work on that project full time with assistance from various members of Assemble who’ve remained based in London. He also employs people who work directly for Granby Workshop who don’t really work on Assemble projects, but still do because they’re still under the aegis of Assemble. It allows us to be a bit free. They will still do projects, whether they are under our name or not. (It’s an) everyone-just-kind-of-takes-credit-for-everything kind of thing. It just kind of works out. But yeah, they’re full-time ceramic technicians and they are experimenting with stuff all the time. Different things.

We had done the houses in Granby, but many of the commercial properties were empty and there’s still a lack of jobs in the area. A lot of manufacturing jobs going overseas and things so the idea was, could we set up a new manufacturing business in Granby and employ local people and see what came of it? So that’s what we did. Lewis moved to Liverpool to do that in 2015 and has continued to work on that project full time with assistance from various members of Assemble who’ve remained based in London. He also employs people who work directly for Granby Workshop who don’t really work on Assemble projects, but still do because they’re still under the aegis of Assemble. It allows us to be a bit free. They will still do projects, whether they are under our name or not. (It’s an) everyone-just-kind-of-takes-credit-for-everything kind of thing. It just kind of works out. But yeah, they’re full-time ceramic technicians and they are experimenting with stuff all the time. Different things.

DM:

It seems like quite often, Assemble projects involve Assemble’s ambitions and then (in different ways and at different scales) other agents (like the Granby Workshop and Armitage Shanks) occupy a position as the consultant and as somebody who really understands the conventions so that Assemble can challenge them.

LS:

Yeah, that’s totally fair. Working with someone like Armitage Shanks is great, but you can only really dabble in it for a few days, and then they’re like, ‘Guys. We do like a million toilets a year, and like we’re busy.’ They’ve got stuff going on. They’ve got the main business that they have to run and I guess with Granby, the other thought about it is that if we build knowledge about a particular process within our own organization, can we actually develop these ideas much more richly?

When you have a higher level of technical knowledge about something, you’re able to imagine influencing the process in different ways.

When you have a higher level of technical knowledge about something, you’re able to imagine influencing the process in different ways.

DM:

How then does Assemble establish boundaries for experimentation? How in creating room for things to go wrong do you decide which avenues to pursue and which to cut off?

LS:

It’s different for every project. It’s a classic problem of course: On the one hand, you want to get it right, while on the other hand, you want to do it quickly, and you need to do it cheaply. You need to do all of these things and also you don’t want to spend your life soul searching over which tint of pastel pink it’s going to be. So I guess it’s about designing.

Most of these projects, we design a process. With Rules of Production, it was a slip casting process and then we just go ahead and roll out the process.

With the A/D/O project, that was a very simple expression of the idea of extruding and the things that we were making, it didn’t even matter what they were. We were just saying, ‘let’s make the biggest pipe we can,’ or ‘I’m gonna do a star.’ We were just making random stuff, and that was the artwork. So the Rules of Production was slightly more tailored, or a slightly more designed process in terms of what was going to be made, or how it was going to be finished.

![]()

![]() Extruded clay at A/D/O

Extruded clay at A/D/O

I guess something like the Yardhouse tiles were even more constrained, wherein we had already developed the concrete mix and made the mould and everything. Then it’s just the colour that changes.

I think there’s a perception that Assemble’s work is generally engaged with members of the public all the time; with people who don’t have any knowledge of the processes. But it’s very rare that we work like that actually. We’re more likely to work with people with specific skills than the general public or with volunteers. We have worked with volunteers, or members of the general public, like at Cafe OTO, which can work as well. Of course with that, you need to think about doing some kind of process that anybody could potentially do and have an input in or be able to express themselves artistically. It’s quite hard. Cafe OTO was a really great project in that way. It was something that people with no background in this kind of thing were able to participate in in a way that was hopefully quite fulfilling.

It’s funny as well, with The Rules of Production, the question kind of implies that the people doing it are maybe not pottery professionals but actually they were. Without saying it, they were pottery professionals. Our firm has two projects, as well, Cineroleum and Folly for a Flyover, we didn’t know what we were doing with either. So things had to be done in such a way for us to get our head around it as well. With those ones we did work with quite a large number of people to produce the thing but that was when Assemble was more of a hobby, and now in our professional existence, it’s less like that really.

Most of these projects, we design a process. With Rules of Production, it was a slip casting process and then we just go ahead and roll out the process.

With the A/D/O project, that was a very simple expression of the idea of extruding and the things that we were making, it didn’t even matter what they were. We were just saying, ‘let’s make the biggest pipe we can,’ or ‘I’m gonna do a star.’ We were just making random stuff, and that was the artwork. So the Rules of Production was slightly more tailored, or a slightly more designed process in terms of what was going to be made, or how it was going to be finished.

I guess something like the Yardhouse tiles were even more constrained, wherein we had already developed the concrete mix and made the mould and everything. Then it’s just the colour that changes.

I think there’s a perception that Assemble’s work is generally engaged with members of the public all the time; with people who don’t have any knowledge of the processes. But it’s very rare that we work like that actually. We’re more likely to work with people with specific skills than the general public or with volunteers. We have worked with volunteers, or members of the general public, like at Cafe OTO, which can work as well. Of course with that, you need to think about doing some kind of process that anybody could potentially do and have an input in or be able to express themselves artistically. It’s quite hard. Cafe OTO was a really great project in that way. It was something that people with no background in this kind of thing were able to participate in in a way that was hopefully quite fulfilling.

It’s funny as well, with The Rules of Production, the question kind of implies that the people doing it are maybe not pottery professionals but actually they were. Without saying it, they were pottery professionals. Our firm has two projects, as well, Cineroleum and Folly for a Flyover, we didn’t know what we were doing with either. So things had to be done in such a way for us to get our head around it as well. With those ones we did work with quite a large number of people to produce the thing but that was when Assemble was more of a hobby, and now in our professional existence, it’s less like that really.

AP:

With A/D/O, was it a project that was mostly about the experimentation and just pushing a method to its limit, without any specific outcome in mind?

Has anything from that extruding experimentation made its way into current or future Assemble projects?

LS:

Good question. I don’t think any of Granby’s products are extruded but you also use the machine just for processing clay. I think that’s the main thing they use it for. I don’t think we’re currently extruding anything directly.

![]()

![]() OTOProjects, 2013

OTOProjects, 2013

OTOProjects, 2013

OTOProjects, 2013AP:

You mentioned Cafe OTO before and we were wondering, in projects like Cafe OTO or Rise&Win, Assemble fosters collaboration between local businesses, craftspeople and suppliers as well as their respective communities in both the process and the product.

How is your approach to the design of these shared, creative spaces different from designing very utilitarian and solitarily-used objects like the toilet for Armitage Shanks? Does Assemble make that distinction?

How is your approach to the design of these shared, creative spaces different from designing very utilitarian and solitarily-used objects like the toilet for Armitage Shanks? Does Assemble make that distinction?

LS:

We do every project differently. We consider our role and we think about what our role is in this particular circumstance. Are we the architect, builder, developer, artist, or code consultant? Sometimes it’s different.

DM:

Given that diversity, does Assemble think of themselves as having a more fluid design ethos, or mission statement or do you have themes that you consciously carry through from project to project?

LS:

Yeah, the mission statement, it’s come up before and we have always struggled to produce one. We do have one. Recently we’ve created one. But it’s very verbose and vague. Previously, those people in Assemble who were resistant to the mission statement argued that each project should be approached differently. That’s always been the discussion. It’s also important that our mission statement never comes as a result of the work, rather than the work is a result of it.

So, rather than having a philosophy or a manifesto we’ve tried to develop our thinking through doing the work itself. Then we can look back and chew over what we were thinking at that time, or what we might think about it. I don’t know if that’s a good way of working. I’m not necessarily recommending it and I don’t necessarily think that it’s a great thing about Assemble, it's just kind of a fact about how we’ve traditionally worked. Maybe it’s important for us, I don’t know. Perhaps it’s considering the process of creation, of design, to be the most important thing or the master of the philosophy I suppose. Rather than trying to set everything out first, in advance, which you’ll be unlikely to be able to do.

So, rather than having a philosophy or a manifesto we’ve tried to develop our thinking through doing the work itself. Then we can look back and chew over what we were thinking at that time, or what we might think about it. I don’t know if that’s a good way of working. I’m not necessarily recommending it and I don’t necessarily think that it’s a great thing about Assemble, it's just kind of a fact about how we’ve traditionally worked. Maybe it’s important for us, I don’t know. Perhaps it’s considering the process of creation, of design, to be the most important thing or the master of the philosophy I suppose. Rather than trying to set everything out first, in advance, which you’ll be unlikely to be able to do.

DM:

Definitely. It seems to be working for Assemble, judging by your collective works.

LS:

It's also to do with the fact that there’s a lot of different people in Assemble. There’s like 16 people and everyone has a different idea about why they’re in Assemble, what kind of projects they want to do, and how they want to move forward with things. I think the different ideas at play and different projects are just expressions of different people, and different people working on different projects at different times has produced results that are both different, but also kind of in conversation with one another. Because obviously we all work together and we influence each other greatly.

---

---